Around 456,000 children and teens under 17 have active epilepsy, according to the CDC.

Senior Raeley Shilling is one of them.

After being diagnosed with epilepsy in 2020 – specifically Juvenile Absence – Shilling has learned a lot about it.

“Epilepsy is a neurological condition that causes unprovoked seizures,” said Shilling.“Different syndromes are associated with it, and there are different types of seizures like absence, myoclonic, tonic clonic, and many more.”

Shilling has been able to keep her disease under control – thanks to medicine – but she noticed something; not about how she was feeling, but how others were acting.

“I noticed a lot of people not understanding,” she said. “I've had teachers who have made jokes about it, I was bullied for my symptoms, and none of my teachers knew at the time what it was. For me, it was a turning point where I thought people don't understand, and I need to use the voice that I have to help them understand.” Shilling started looking for ways to make her voice heard. From her research, she located Teens Speak Up, an advocacy initiative from the Epilepsy Foundation.

“I saw it on the Epilepsy Foundation's website, and I first applied just as a joke, not really thinking I would get it, and then I got the email that I was chosen. I was super excited,” Shilling recalled.

As the Teens Speak Up representative for Indiana, Shilling has had many opportunities to share her story, such as news interviews, visiting children with epilepsy in hospitals, running social media accounts, speaking at walks, and much more. One of her biggest opportunities was going to Washington DC for the Teens Speak Up and Public Policy Institute Conference.

“I was in DC for three days for the actual conference,” said Shilling. “The first two days, we just spoke with each other. There were a bunch of different teens, and we all got to know each other and relate to each other. It helped a lot of us feel less alone. The last day we were there, we went to Capitol Hill and spoke with Congress.”

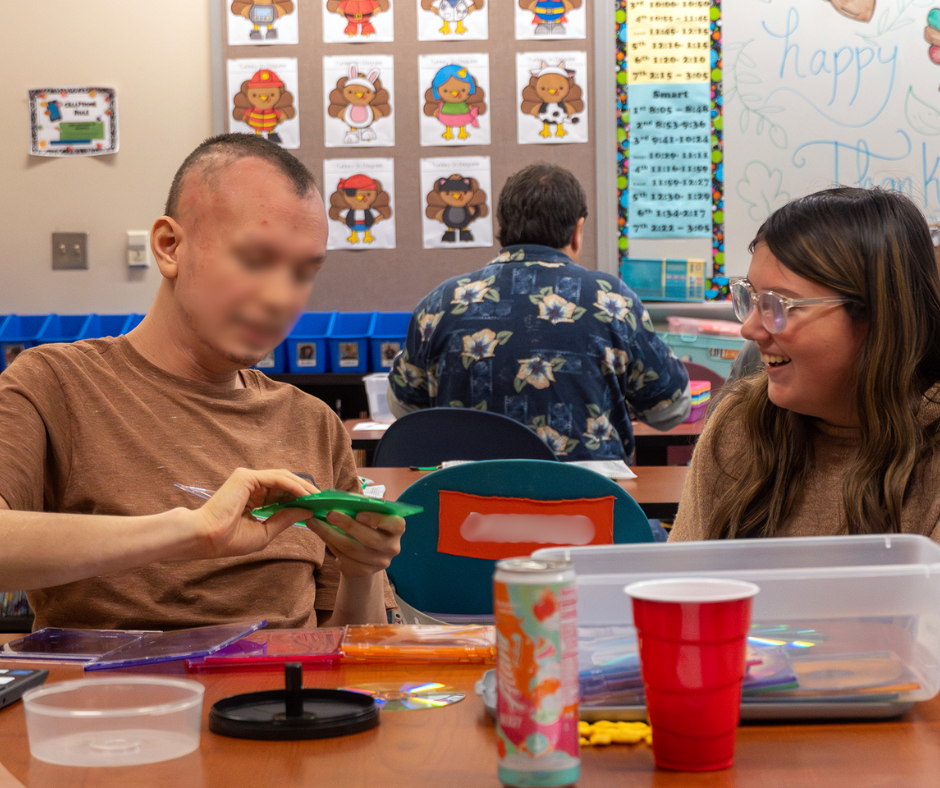

Through peer tutoring, Shilling has been able to see her positive impact on others.

“There are kids in Peer Tutoring that do have epilepsy like me, and when parents would email me and ask me for advice because they didn't know how to navigate getting their child's diagnosis, it just made me feel better because I was helping them be able to help their child,” she said.

Shilling hopes that through her work, she can decrease the stigma surrounding invisible illness.

“I think that with invisible illnesses, a lot of people will just dismiss it and tell you it's not valid, or you don't look disabled. Many people think that if it's not visible, it doesn't exist, so I want to use my voice to help get it across that just because it isn’t visible to the naked eye doesn't mean that it doesn't exist. It’s still there, for sure.”

For people who are ready to start speaking up for themselves and others, Shilling says to just go for it.

“At the end of the day, your voice is what matters, and you have to be able to use your voice and advocate for change, or change won't happen,” she said. “Nobody can just read your mind and know that you want change; you have to be able to speak up. I was nervous at first, but I also knew what I needed to do for myself and others.”

Story by Reese Napier